Will dementia ever be preventable?

Researchers, academics, scientists, doctors– everyone who works with the brain – are putting their heads together to find out. As it stands today, major actors in public health, like the WHO and the CDC, have been developing strategies to protect against cognitive decline. The task now is to find the best possible ways to practically implement these activities and maximise their impact.

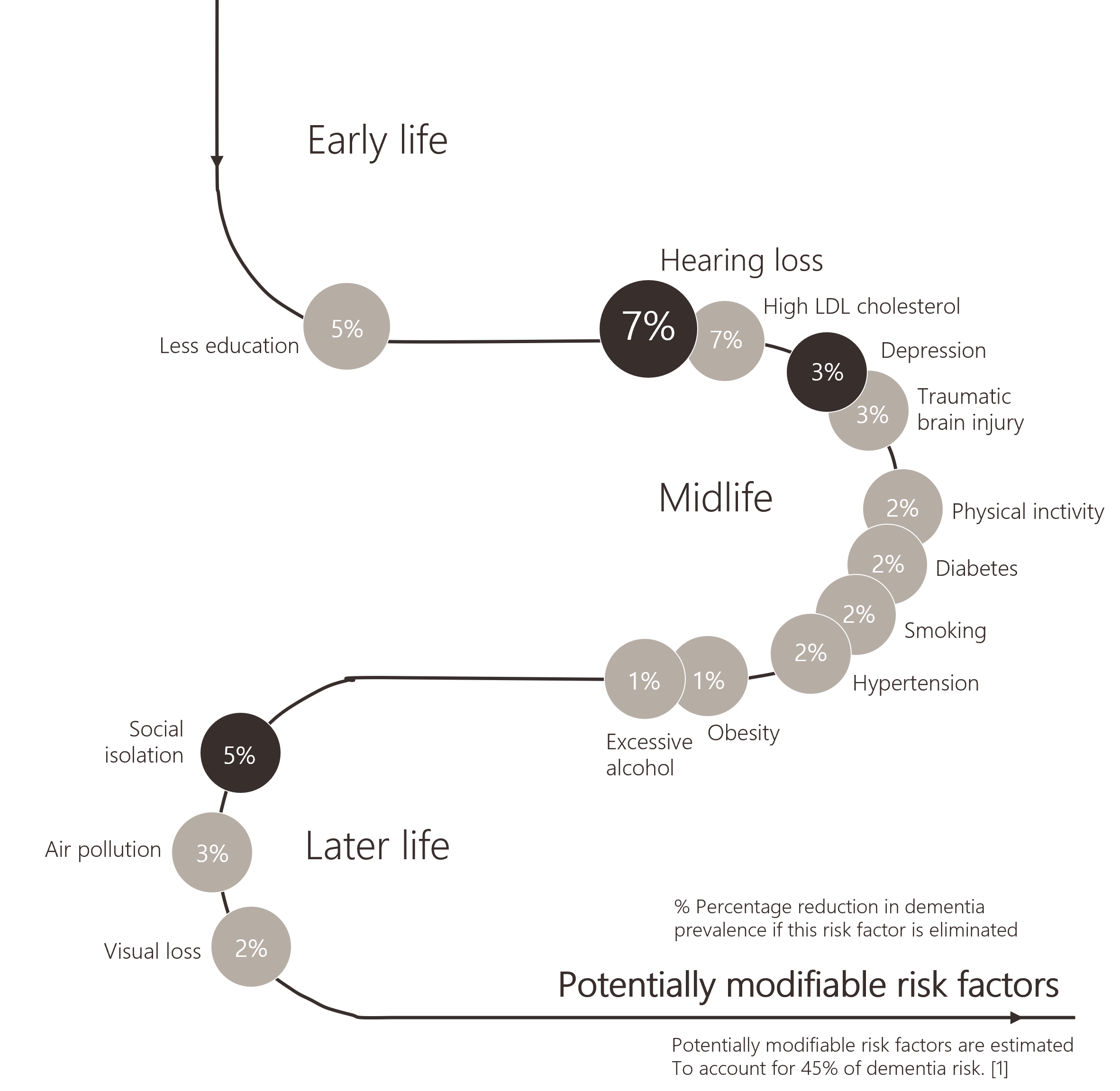

The wealth of data about cognitive function in later life has left us more informed than ever about the risk factors of dementia. A total of 14 potentially modifiable risk factors have been identified by researchers, which potentially could reduce the number of dementia cases worldwide by 45% if eradicated.

These findings, published by the Lancet Commission in a 2024 report1, both expanded our knowledge and provided a foundation for various prevention strategies and initiatives. But what about that other 55%? The risks that make up this percentage are currently unknown, but it is suspected that they could be those factors that are harder to quantify, such as genetic predisposition.

There is still a sizeable question mark around the entire story of dementia risk factors. But the insight into those that are potentially modifiable gives us tangible direction about where to direct efforts to make a real difference.

The 14 potentially modifiable risk factors from the 2024 report on dementia prevention, intervention, and care by the Lancet Commission are:

- Less education

- Hearing loss

- High LDL cholesterol

- Depression

- Traumatic brain injury

- Physical inactivity

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Hypertension

- Obesity

- Excessive alcohol

- Social isolation

- Air pollution

- Visual loss

How early should we plan for later life?

Some of the 14 factors are what many of us would assume them to be – things that pose a risk to health generally –smoking, alcohol, diabetes. Whereas others extend way past what might generally be assumed to lead to cognitive decline – air pollution, hypertension, and even social isolation.

Thinking about the things that might put us at risk of eventually developing dementia is one thing. Considering when these factors actually become risks is another. By putting the risk factors into a life-course model, we can see that many of these risk factors start way earlier than we expect – and we mean way earlier.

The risk factor that comes first in the life course, and accounts for 5% is less education. This leaves us with a strong reason to believe that a predisposition for dementia might begin much earlier than is often talked about. To have a maximum impact, 11 of the 14 risk factors would need to be addressed in early to mid-life and together account for over half of the 45% total risk. Sitting in this age range is one of the most significant risk factors for developing dementia: hearing loss.

Enter: hearing aids

The line of thinking is that by eliminating hearing loss, we could on that basis alone reduce the number of dementia cases by 7%, according to The Lancet authors. This is where hearing aids come in. In their review, the authors included multiple studies examining the influence of hearing aids on cognitive decline in people with hearing loss. The consensus was that hearing aid use is protective against hearing loss. Seemingly, of all the factors protecting against cognitive decline in people with hearing loss, hearing aid use was found to be one of the largest.

"Eliminating hearing loss could alone potentially reduce the number of dementia cases by up to 7% – making it one of the most significant potentially modifiable risk factors"

This 7% reduction in dementia prevalence stole the spotlight when the paper was published, and for good reason. However, other researchers in the field have commented on, and in some cases, countered this statistic. In a 2024 article, authors Dawes and Munro challenge this statistic by stating it is a proportional factor to the number of people with hearing loss compared to the other issues in each country2. Meaning, in some countries addressing hearing loss might have a proportionally smaller impact on dementia cases compared to some of the other risk factors. It's an important point to consider.

However, the argument remains that regardless of the potential change in risk across the world, addressing untreated hearing loss continues to have an important role in reducing the prevalence and burden of dementia.

Of course, it is natural to read about all of the ways we might be putting ourselves at risk for developing dementia and start to fret. However, what we can take away from this model is the reassurance that many of these risk factors are also preventable. Which is why it is fundamental that people at all ages of life are made aware about the risks and when they may become at risk.

Then, we can prepare. As the authors themselves state "It is never too early and never too late in the life course for dementia prevention."

Action on every front

As is the case with our overall health, there is no one, sure-fire route to a life lived in perfect health, or with perfect cognitive function in later life. However, like with many other health issues and diseases, many of the risk factors of dementia can be reduced by leading a healthy life.

Caring for our body, and our brain, is something that needs to happen holistically, with consideration for the many influencing factors. Preventing dementia is not something that happens in a silo. It requires action from every level, starting at with the individual and extending all the way to public health policy.

"It is never too early and never too late in the life course for dementia prevention"

Let's take hearing care as the prime example. The Lancet paper's authors suggest initiatives ranging from what people with hearing loss can do themselves, all the way to how governments can rethink their public health strategies. And they're not the only ones. The authors behind the World Alzheimer Report, in their 2023 edition, also highlight the game-changing influence of treating hearing loss with hearing aids to slow cognitive decline in a way that is cost-effective and scalable.

Their suggestions echo those of The Lancet, in an encouragement to governments and healthcare systems to improve access to hearing devices, particularly in lower- and idle-income countries3.

Recommendations backed by The Lancet authors' findings:

- Individuals themselves should ensure they get their hearing checked and wear the hearing aids they are prescribed.

- Strategies, initiatives, and policies that encourage individuals to get their hearing checked before retirement age

- Scrutinization of the risk of hearing loss throughout the life course

- Helping individuals overcome the challenges that they encounter when trying to wear hearing aids.

Following this advice can put individuals and audiologists alike in a stronger position to minimise the risk associated with hearing loss.

Publications like the 14-risk factor model for developing dementia only strengthen the LISTEN TO THIS mission. By sharing findings like these, our ambition is to put information into the hands of those who can do something about it and mobilise collective action. After all, nothing works harder than our brains – it's the least we can do to say thank you.

Keep an eye out for the next edition of this BEYOND THE DATA series for a new research digest in the escalating hearing and brain health story. Read more insights on hearing and brain health.

Sign up to our newsletter to be notified about the latest news and research.

¹ Livingston, G. et al. (2024) Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission, The Lancet, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736%2824%2901296-0

² Dawes P, Munro KJ. Hearing Loss and Dementia: Where to From Here? Ear Hear. 2024 May-Jun 01;45(3):529-536. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001494. Epub 2024 Feb 21. PMID: 38379156; PMCID: PMC11008448.

³ https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2023/